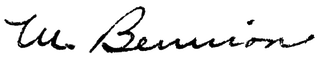

1909-1910 NAVAL SHAPSHOOTER MEDAL

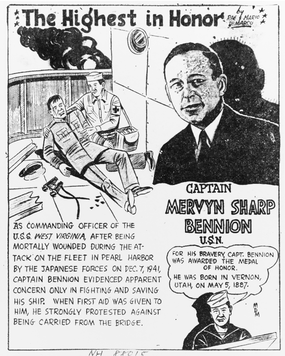

Captain

|

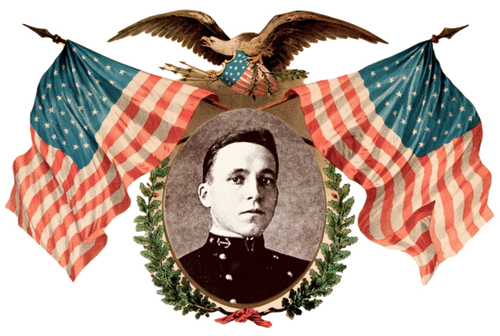

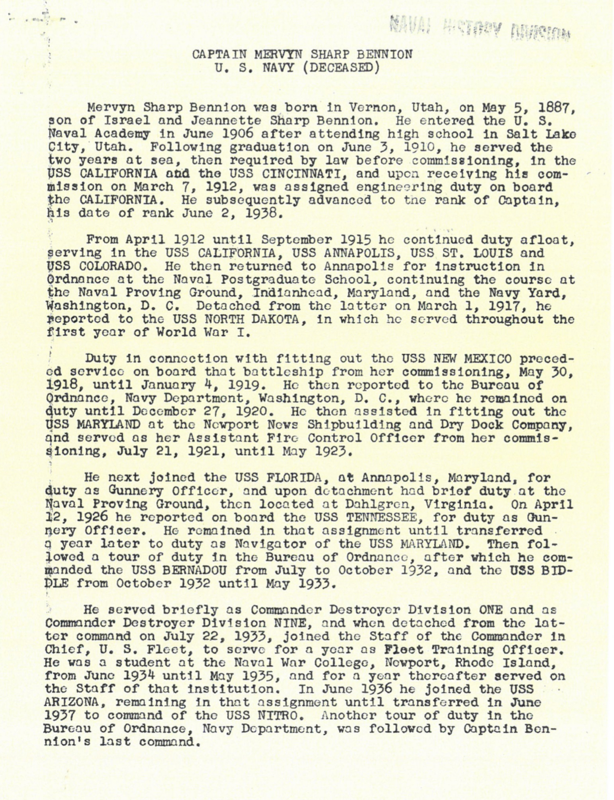

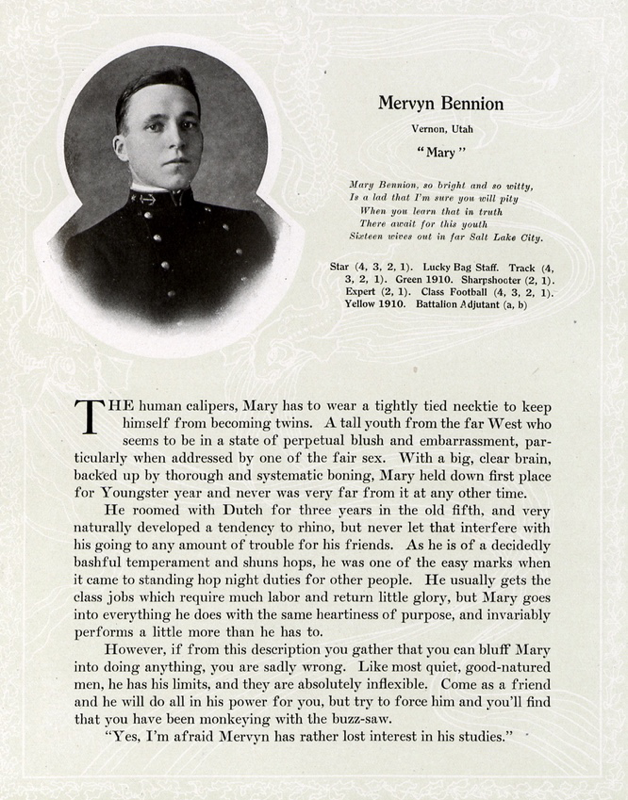

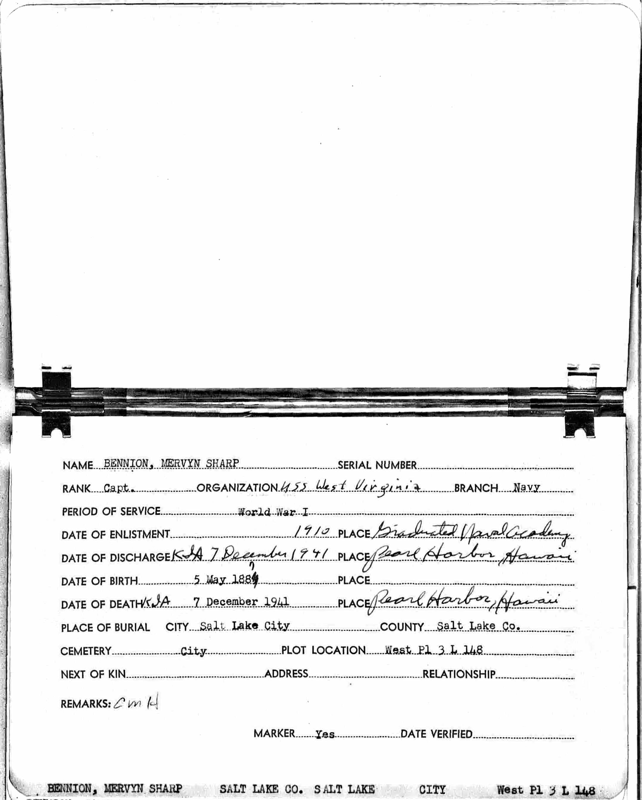

United States Navy Captain Mervyn Sharp Bennion was born in Vernon, Tooele County, Utah, a small farming and stock raising community on the edge of the desert on May 5th 1887, to Israel and Jeannette Sharp Bennion. Mervyn worked on his Uncle Archie’s Nevada ranch as a teenager and graduated from Latter Day Saints high school in Salt Lake City, Utah.

|

|

Mervyn reached Annapolis in June, 1906, and was put through the meticulous and trying experience of getting outfitted, drilled and marshaled about. Soon he sailed on a few weeks cruise down Chesapeake Bay on the tall-masted schooner U.S.S. Severn, where he was drilled in nautical terms and practices, particularly in climbing masts, furling and reefing sails, in rope lore, in swabbing decks and standing watch. |

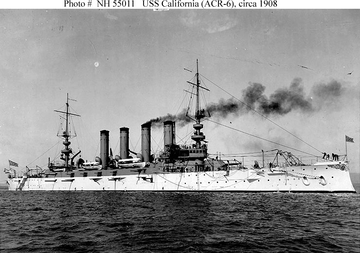

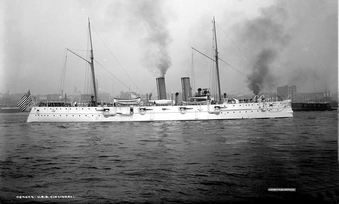

Following graduation on June 3rd 1910, he served the two years at sea, then required by law before commissioning, on the USS California and USS Cincinnati, and upon receiving his commission on March 7, 1912, was assigned engineering duty on board the California.

|

|

From April 1912 until September 1915 he continued duty afloat, serving in USS California, USS Annapolis, USS St. Louis and USS Colorado. He then returned to Annapolis for instruction in Ordnance at the Naval Postgraduate School, continuing the course at the Naval Proving Ground, Indianhead, Maryland, and the Navy Yard, Washington, DC. |

|

He then assisted in fitting out USS Maryland at the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company, and served as her Assistant Fire Control Officer from her commissioning, July 21, 1921, until May 1923.

|

|

He next joined the USS Florida, at Annapolis, Maryland, for duty as Gunnery Officer, and upon detachment had brief duty at the Naval Proving Ground, then located at Dahlgren, Virginia. On April 12, 1926 he reported on board the USS Tennessee, for duty as Gunnery Officer.

|

He remained in that assignment until transferred a year later to duty as Navigator of USS Maryland.

|

Then followed a tour of duty in the Bureau of Ordnance, after which he commanded the USS Bernadou from July to October 1932, and USS Biddle from October 1932 until May 1933. He served briefly as Commander Destroyer Division ONE and as Commander Destroyer Division NINE, and when detached from the latter command on July 22, 1933, joined the Staff of the Commander in Chief, US Fleet, to serve for a year as Fleet Training Officer.

|

|

He was a student at the Naval War College, Newport, Rhode Island, from June 1934 until May 1935, and for a year thereafter served on the Staff of that institution. In June 1936 he joined the crew of the famous USS Arizona, remaining in that assignment until transferred in June 1937 to command of USS Nitro. |

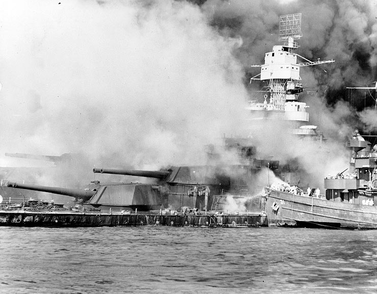

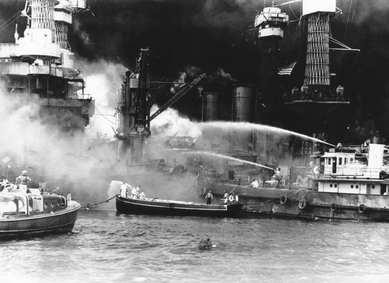

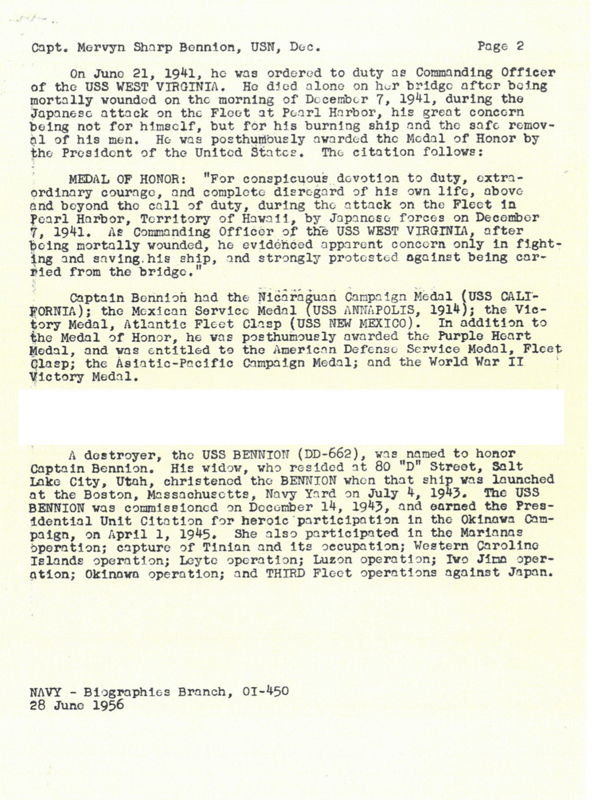

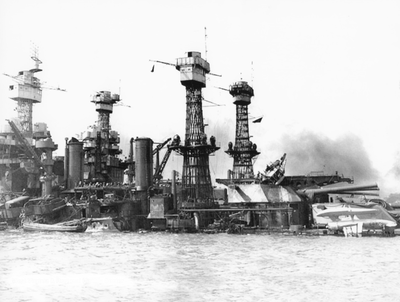

The ship was well handled to prevent capsizing and to keep damage from fire to a minimum, Admiral Furlong, one of the commanders at Pearl Harbor, gave the West Virginia’s guns credit for bringing down 20 or 30 Japanese planes. Only two lives were lost from the ship’s complement of officers and men. . Captain Bennion and one seaman. The wounded were attended to promptly and evacuated from the ship with dispatch. Mervyn was courageous and cheerful to the last moment of consciousness and his spirit was reflected in the conduct of his crew. When the first attack was over he allowed himself to be placed on a cot and the cot to be moved under a protecting shelter on the deck. There he remained during the second Japanese attack which occurred an hour after the first one. He resisted all efforts to remove him from the bridge with a firmness and vigor that astonished officers who thought they knew him well but did not realize how much force there lay behind his gentle ways. He talked only of the ship and the men, how the fight was going, what guns were out of action, how to get them in operation again, casualties in the gun crews and how to replace them, who was wounded, what care the wounded were receiving and provisions for evacuating them from the ship, the fate of other ships, the number of enemy planes shot down, the danger of fire from burning oil drifting around the West Virginia from the exploded Arizona, satisfaction over the handling of the ship, satisfaction with the effectiveness of the gun crews in shooting down attacking planes, satisfaction with the conduct under fire of officers and men of the ship. His only expression of regrets were of horror for the treachery of the Japanese and of concern because of this paralyzing loss of warships.

|

Medal of Honor Citation:

“For conspicuous devotion to duty, extraordinary courage, and complete disregard of his own life, above and beyond the call of duty, during the attack on the Fleet in Pearl Harbor, Territory of Hawaii, by Japanese forces on December 7, 1941. As Commanding Officer of the USS West Virginia, after being mortally wounded, he evidenced apparent concern only in fighting and saving his ship, and strongly protested against being carried from the bridge.” |