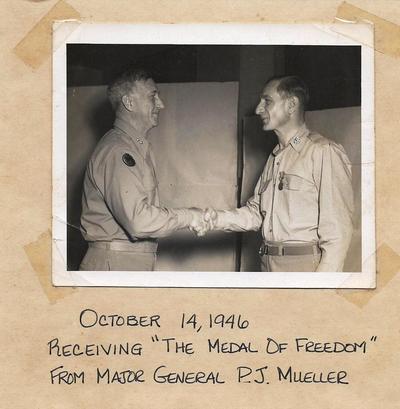

1946 WhiteHead & Hoag Medal of Freedom

Irving Williams

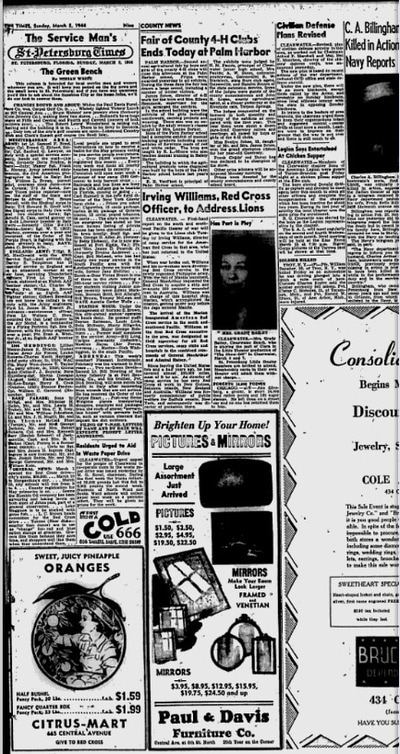

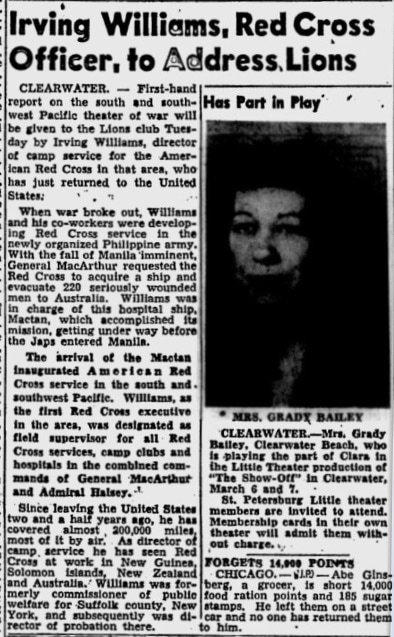

Irving Williams was born in Manhattan, New York May 8, 1901. He was the commissioner of Public Welfare of Suffolk County, NY back in the mid to late 1930's. Irving Williams was the Field Director for the American Red Cross during World War II for which he was awarded the Medal of Freedom Oct. 14, 1946. Williams was in Command of the Red Cross during the evacuation of wounded soldiers from the Philippines aboard the S.S. Mactan December 31st 1941. Known as "The Great Escape of the S.S. Mactan". Including Irving Williams Civil Service working for the American Red Cross, he also worked for the United Seaman's Service.

William's died Dec. 13, 1988 in White Stone, Virginia. He was cremated and his ashes remain with family to this day.

William's died Dec. 13, 1988 in White Stone, Virginia. He was cremated and his ashes remain with family to this day.

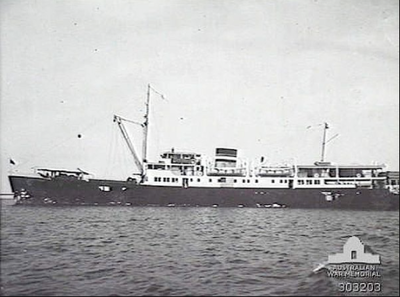

The Great Escape of the S.S. Mactan

On 23 December General MacArthur decided to evacuate Manila, which he had declared an open city on 18 December, and on Christmas Eve he and his headquarters evacuated the city. Patients and medical personnel had begun moving to Bataan. On 25 December most of the medical personnel remaining had evacuated and by the 28th the facilities on Corregidor had become overcrowded with the last patients and personnel evacuated from Manila on New Year's Eve. MacArthur directed that the worst cases be selected for an attempt to evacuate them to Australia.

Late at night, on December 31, 1941, an old ship prepared to weigh anchor to escape Manila. Its destination was Sydney, Australia. On board, were 224 wounded USAFFE soldiers (134 of them Americans and 90 of whom were Filipinos); 67 crew members, all Filipino, and 25 medical and Red Cross personnel, all Filipino except for one American nurse, and some others.

The ship was the S.S. Mactan. Its journey represents one of the great escapes of World War II.

On the morning of December 24, some twenty Red Cross volunteer women were in the official residence of Francis B. Sayre, High Commissioner to the Philippines, packing Christmas gifts for soldiers and sailors in hospitals in and around Manila. Mrs. Sayre was in charge of the group.

Suddenly, at eleven o’clock, Mrs. Sayre looked up from her task at the tables to see her husband standing in the patio doorway beck- oning to her. She slipped quietly out of the room and stood in the patio. “I have an urgent message from General MacArthur,” said Mr. Sayre in a low voice. “The city may fall, and we must be ready to leave for Corregidor at one-thirty!”

Mrs. Sayre was stunned. “But we must finish these bags. They’re the only Christmas our boys will have.”

“Pack as quickly as you can,” he said and left hurriedly. Mrs. Sayre went back to the tables. The women worked quickly, and in silence, to complete their task before the daily noon Japanese air raid over Manila.

The treasure bags, as they were called, made hundreds of American and Filipino soldiers and sailors happier in their hospital wards that dark Christmas Day. Irving Williams helped Gray Ladies make the distribution in the Sternberg General Hospital. The work was under the direction of Miss Catherine L. Nau, of Pittsburgh assistant field director at the hospital, who later was to distinguish herself for her work among the troops on Bataan and Corregidor, before the Japanese interned her.

Of the gift distribution at Sternberg General Hospital, Irving Williams said, “I shall never forget the boys’ beaming faces and delighted eyes as we went from ward to ward. The simple comfort articles meant so much to these boys, who had lost all of their possessions on the field of battle.”

The Philippine Diary Project contains General Basilio J. Valdes’ diary entry for December 24, 1941, giving the Filipino side of that day’s hectic events.

Valdes returning to Manila to contact the Red Cross:

Not until three days later December 28 did Williams know that these same boys would be entrusted to his care on one of the most hazardous missions of the war. Major General Basilio Valdes, then commanding general of the Filipino Army, came straight from MacArthur’s headquarters on Corregidor with the urgent request that the American Red Cross undertake to transport all serious casualties from the Sternberg General Hospital to Australia. President Manuel Quezon of the Philippine Commonwealth helped the Red Cross locate the Mactan.

Working under threat of Manila’s imminent occupation by Japanese troops, Williams and his Red Cross associates, and the crews under them, performed a miracle of speed in outfitting the Mactan as a hospital ship. Simultaneously, steps were taken to fulfill the obligations of international law governing hospital ships: The Mactan was painted white with a red band around the vessel and large red crosses on her sides and top decks; a charter agreement was made between the American Red Cross and the ship’s owners; the ship was commissioned in the name of the President of the United States; in accordance with cabled instructions from Chairman Norman H. Davis in the name of the American Red Cross, the Japanese Government was apprized of the ship’s description and course; all contraband was dumped overboard; and the Swiss Consul, after a diligent inspection as the representative of United States interests, gave his official blessings.

Although the Red Cross was given clearance for the ship to leave by a Japanese commander, this was the first hospital ship to transport wounded soldiers in a war that the United States had just entered. There was great concern that the ship would be attacked by air or torpedo. Those aboard the ship rang in New Year’s Day 1942 to the sight of Manila in flames as the Americans blew up gasoline storage tanks to keep the supplies out of enemy hands.

The journey was fraught with peril. The ship had to zigzag through a maze of mines just to leave Manila Bay, following a Navy ship for guidance, and had a close call when it made a wrong turn in the darkness. The ship was infested with cockroaches, red ants, and copra beetles. Violent storms tossed the ship and drenched the patients on their cots on the decks, sheltered only by canvas. There was a fire in the engine room, and for a time those aboard prepared to abandon ship. Two wounded soldiers died from their injuries during the crossing, and a depressed Filipino soldier committed suicide by jumping overboard.

On Jan. 27, 1942, the Mactan arrived in Sydney Harbor to much fanfare, especially after newspapers had falsely reported that the ship had been attacked multiple times. Despite the primitive conditions aboard the vessel, the wounded soldiers arrived in very good condition and were quickly taken to a hospital on land. The Mactan’s voyage made headlines in the United States.

Late at night, on December 31, 1941, an old ship prepared to weigh anchor to escape Manila. Its destination was Sydney, Australia. On board, were 224 wounded USAFFE soldiers (134 of them Americans and 90 of whom were Filipinos); 67 crew members, all Filipino, and 25 medical and Red Cross personnel, all Filipino except for one American nurse, and some others.

The ship was the S.S. Mactan. Its journey represents one of the great escapes of World War II.

On the morning of December 24, some twenty Red Cross volunteer women were in the official residence of Francis B. Sayre, High Commissioner to the Philippines, packing Christmas gifts for soldiers and sailors in hospitals in and around Manila. Mrs. Sayre was in charge of the group.

Suddenly, at eleven o’clock, Mrs. Sayre looked up from her task at the tables to see her husband standing in the patio doorway beck- oning to her. She slipped quietly out of the room and stood in the patio. “I have an urgent message from General MacArthur,” said Mr. Sayre in a low voice. “The city may fall, and we must be ready to leave for Corregidor at one-thirty!”

Mrs. Sayre was stunned. “But we must finish these bags. They’re the only Christmas our boys will have.”

“Pack as quickly as you can,” he said and left hurriedly. Mrs. Sayre went back to the tables. The women worked quickly, and in silence, to complete their task before the daily noon Japanese air raid over Manila.

The treasure bags, as they were called, made hundreds of American and Filipino soldiers and sailors happier in their hospital wards that dark Christmas Day. Irving Williams helped Gray Ladies make the distribution in the Sternberg General Hospital. The work was under the direction of Miss Catherine L. Nau, of Pittsburgh assistant field director at the hospital, who later was to distinguish herself for her work among the troops on Bataan and Corregidor, before the Japanese interned her.

Of the gift distribution at Sternberg General Hospital, Irving Williams said, “I shall never forget the boys’ beaming faces and delighted eyes as we went from ward to ward. The simple comfort articles meant so much to these boys, who had lost all of their possessions on the field of battle.”

The Philippine Diary Project contains General Basilio J. Valdes’ diary entry for December 24, 1941, giving the Filipino side of that day’s hectic events.

Valdes returning to Manila to contact the Red Cross:

Not until three days later December 28 did Williams know that these same boys would be entrusted to his care on one of the most hazardous missions of the war. Major General Basilio Valdes, then commanding general of the Filipino Army, came straight from MacArthur’s headquarters on Corregidor with the urgent request that the American Red Cross undertake to transport all serious casualties from the Sternberg General Hospital to Australia. President Manuel Quezon of the Philippine Commonwealth helped the Red Cross locate the Mactan.

Working under threat of Manila’s imminent occupation by Japanese troops, Williams and his Red Cross associates, and the crews under them, performed a miracle of speed in outfitting the Mactan as a hospital ship. Simultaneously, steps were taken to fulfill the obligations of international law governing hospital ships: The Mactan was painted white with a red band around the vessel and large red crosses on her sides and top decks; a charter agreement was made between the American Red Cross and the ship’s owners; the ship was commissioned in the name of the President of the United States; in accordance with cabled instructions from Chairman Norman H. Davis in the name of the American Red Cross, the Japanese Government was apprized of the ship’s description and course; all contraband was dumped overboard; and the Swiss Consul, after a diligent inspection as the representative of United States interests, gave his official blessings.

Although the Red Cross was given clearance for the ship to leave by a Japanese commander, this was the first hospital ship to transport wounded soldiers in a war that the United States had just entered. There was great concern that the ship would be attacked by air or torpedo. Those aboard the ship rang in New Year’s Day 1942 to the sight of Manila in flames as the Americans blew up gasoline storage tanks to keep the supplies out of enemy hands.

The journey was fraught with peril. The ship had to zigzag through a maze of mines just to leave Manila Bay, following a Navy ship for guidance, and had a close call when it made a wrong turn in the darkness. The ship was infested with cockroaches, red ants, and copra beetles. Violent storms tossed the ship and drenched the patients on their cots on the decks, sheltered only by canvas. There was a fire in the engine room, and for a time those aboard prepared to abandon ship. Two wounded soldiers died from their injuries during the crossing, and a depressed Filipino soldier committed suicide by jumping overboard.

On Jan. 27, 1942, the Mactan arrived in Sydney Harbor to much fanfare, especially after newspapers had falsely reported that the ship had been attacked multiple times. Despite the primitive conditions aboard the vessel, the wounded soldiers arrived in very good condition and were quickly taken to a hospital on land. The Mactan’s voyage made headlines in the United States.

S.S. Mactan

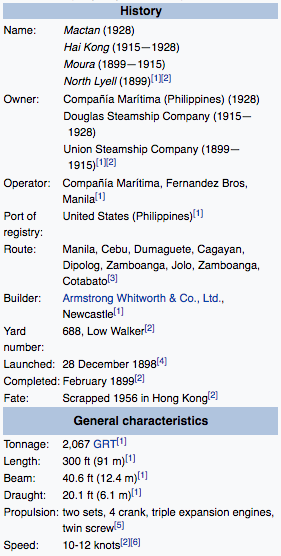

SS Mactan was launched 28 December 1898 as the passenger/cargo ship North Lyell for North Mount Lyell Copper Co.Ltd. intended for service between the west coast of Tasmania and Melbourne. The company no longer needed the ship on delivery in 1899 with resulting sale to Union Steamship Company of New Zealand Ltd. and renaming as Moura. In 1915 upon sale to the Douglas Steamship Company, Ltd. of Hong Kong she was renamed Hai Hong. Upon sale to Philippine operators in 1928 the ship gained the final name Mactan.

As Mactan the ship made news and history during the first months of war in the Pacific 1941-1942 as the first hospital ship, under charter to the American Red Cross through its Philippine Red Cross representative, in the Southwest Pacific Area. On a single voyage as the improvised hospital ship Mactan she evacuated 224 critically wounded patients, "the worst cases," along with a number of Filipino doctors and nurses serving with the Army, a U.S. Army doctor and two Army nurses from the burning city of Manila just prior to its occupation by Japanese troops.

As Mactan the ship made news and history during the first months of war in the Pacific 1941-1942 as the first hospital ship, under charter to the American Red Cross through its Philippine Red Cross representative, in the Southwest Pacific Area. On a single voyage as the improvised hospital ship Mactan she evacuated 224 critically wounded patients, "the worst cases," along with a number of Filipino doctors and nurses serving with the Army, a U.S. Army doctor and two Army nurses from the burning city of Manila just prior to its occupation by Japanese troops.